The Global Tapestry of Europe (1200 to 1450)

The main difference is that Europe is a continent, that is, a physical space that is made up of the countries that inhabit the region, while the European Union is a geopolitical organization that is made up of some countries of the continent.

Difference Between Europe and European Union

Europe Today in Facts and Numbers

Largest and Smallest Countries in Europe

Russia is the largest nation in Europe by both area and population.

Vatican City is the smallest country in Europe by both size and population.

Bodies of Water in Europe

Hornindalsvatnet, Norway, is the deepest lake in Europe.

Lake Ladoga, Russia, is the largest lake in Europe.

Hottest and Coldest Places in Europe

The hottest place in Europe is Valletta in Malta.

Reykjavík, Iceland, is the coldest place in Europe.

An Overview of Europe 1200 to 1450

1200-1450 is the end of Medieval Europe with its castles, knights and chivalry. It is still backwards.

While they will soon have global empires by the end of the NEXT period. For now, it’s pretty much in the dark age.

Trade with the rest of the world is kind of limited, but does exist such as Venetians trading with the Middle East, and during this period we see Mongol Invasions, The Black Death, the Crusades, and the 100 Years War.

It’s a dismal period in Europe’s history. We will look at some of the most important places, people, and events, and then consider some theories for population growth and decline during this period.

Europe before 1347 CE

Europe had experienced a remarkable period of expansion during the High Middle Ages (1050-1300 CE) but that age of growth reached its limit in the later part of the thirteenth century (the late 1200’s CE). By then, good farmland had been overworked, and new fields were proving only marginally productive. As the population began to surpass the capacity of the land to feed its inhabitants, famine was imminent.

Worse yet, the climate of Europe was for reasons which are still unclear entering a cooling phase. Whereas in the High Middle Ages a warm, dry climate had predominated, by the turn of the fourteenth century global weather patterns changed for the colder and wetter. Scientists today find evidence of this so-called “Little Ice Age,” in polar and Alpine glaciers which the data show began to advance at this time. Moreover, historical records from the day confirm that the winter of 1306-7 was unusually frigid, the first such lingering cold snap Europe had endured in nearly three centuries.

While the drop in global temperature was probably no more than one degree on average, it was enough to make a significant impact on agriculture. For instance, grain and cereal production had to be abandoned in Scandinavia, and viticulture (wine-production) became impossible in England, as it still is for the most part. Not only cooler but wetter, too, the change in climate brought with it increased rainfall which precipitated other problems, such as flooding. In particular, the Arno River which flows through Florence (central Italy) swept away many bridges with the force of its waters.

But the first real pan-European catastrophe resulting from the onset of the “Little Ice Age” was a widespread failure of crops. Beginning in 1315, the weather was so rainy that most grains sown in the ground suffered root rot, if they germinated at all. Also, the lack of sun, high humidity and cooler temperatures meant water evaporated at a slower rate, which caused salt production to drop. Less salt made it more difficult to preserve meats and that, combined with the losses in agriculture, led to famine by year’s end.

When the same happened again in 1316 and then once more in 1317, peasants were forced to eat their seed grain. With little hope of recovery even if weather improved, despair spread across the continent. Frantic to survive, people ate cats, dogs, rats and, according to some historical records, their own children. In places, the announcement of a criminal’s execution was seen as an invitation to dinner.

Later branded the Famine of 1315-1317, this disaster marked the beginning of a decrease in European population that would last more than a century and a half. Many cities were hard hit—for instance, in Ypres (Flanders) a tenth of the population died in six months and in Halesowen (England) the population dropped by fifteen percent during this period—all this led to general de-urbanization across the continent.

Nevertheless, these emaciated souls could not have known that worse, far worse, lurked on the horizon. A holocaust of unprecedented fury was stalking them and their children. Out in the hinterland of Asia there was a biological menace massing, a blight that would forever change the face of Europe, the bubonic plague.

(From: https://www.usu.edu/markdamen/1320hist&civ/chapters/06plague.htm)

| Important Terms | Notable Places | Notable People | Notable Events |

| Feudalism Serfdom Magna Carta Byzantine Empire | Venice Cordoba Kievan Rus Hanseatic League | Marco Polo Margery Kempe Prince Henry Gutenberg | The Black Death The Crusades The 100 Years War Little Ice Age |

Europe in The 21st Century

Geography

Europe is the second smallest of the world’s continents.

It is composed of the westward-projecting peninsulas of Eurasia (the great landmass that it shares with Asia).

It occupies nearly one-fifteenth of the world’s total land area.

It is bordered on the north by the Arctic Ocean, on the west by the Atlantic Ocean, and on the south (west to east) by the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, the Kuma-Manych Depression, and the Caspian Sea.

The continent’s eastern boundary (north to south) runs along the Ural Mountains and then roughly southwest along the Emba (Zhem) River, terminating at the northern Caspian coast.

Among the continents, Europe is an anomaly. Larger only than Australia. It is a small appendage of Eurasia. Yet the peninsular and insular western extremity of the continent provides a relatively genial human habitat.

The long processes of human history came to mark off the region as the home of a distinctive civilization. In spite of its internal diversity, Europe has thus functioned, from the time it first emerged in the human consciousness, as a world apart.

More here.

Populations

There was a total European population of 744 million as of 2018.

There are over 250 languages indigenous to Europe, and most belong to the Indo-European language. The three largest phyla (major group / family) of the Indo-European language family in Europe are Romance, Germanic, and Slavic; they have more than 200 million speakers each, and together account for close to 90% of Europeans.

Smaller phyla of Indo-European languages are found in Europe including Hellenic (Greek, c. 13 million), Baltic (c. 7 million), Albanian (c. 7.5 million), Celtic (c. 4 million), and Armenian (c. 4 million). Indo-Aryan, though a large subfamily of Indo-European, has a relatively small number of languages in Europe, and a small number of speakers (Romani, c. 1.5 million). However, a number of Indo-Aryan languages not native to Europe are spoken in Europe today.

More here.

Of the approximately 45 million Europeans speaking non-Indo-European languages, most speak languages within either the Uralic or Turkic families. Still smaller groups — such as Basque , Semitic languages (Maltese, c. 0.5 million), and various languages of the Caucasus — account for less than 1% of the European population among them.

Immigration has added sizeable communities of speakers of African and Asian languages, amounting to about 4% of the population, with Arabic being the most widely spoken of them.

Five languages have more than 50 million native speakers in Europe: Russian, English, French, Italian, and German. Russian is the most-spoken native language in Europe, and English has the largest number of speakers in total, including some 200 million speakers of English as a second or foreign language.

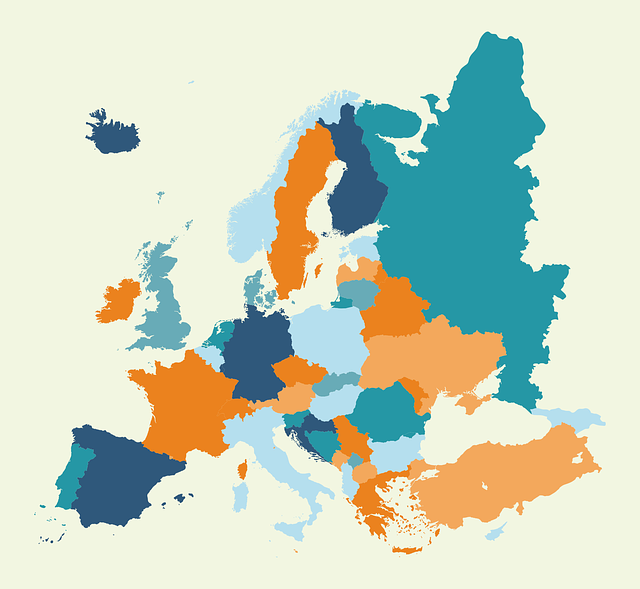

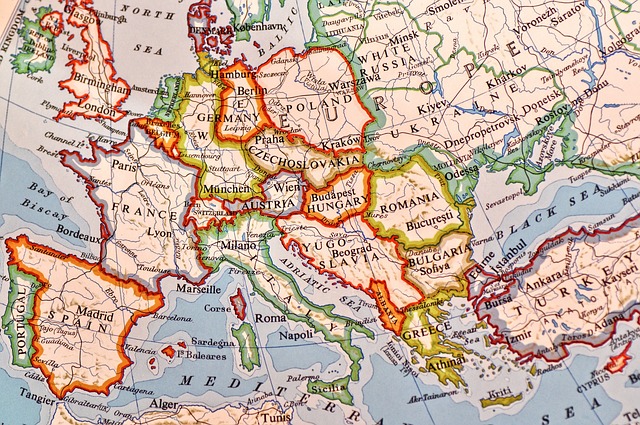

Here are some political maps.

Europe in 1200 to 1450

Feudalism

This was the dominant social system in medieval Europe, in which the nobility held lands from the Crown in exchange for military service, and vassals (land holders) were in turn tenants of the nobles. The peasants: villeins (tenant who were entirely subject to a lord or manor and to whom they paid dues and services in return for land) or serfs (agricultural laborer bound under to work on their lord’s estate) were obliged to live on their lord’s land and give him homage, labor, and a share of the produce, potentially in exchange for military protection.

Serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism (a system based on the manor, a self-sufficient landed estate controlled by a lord). It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery.

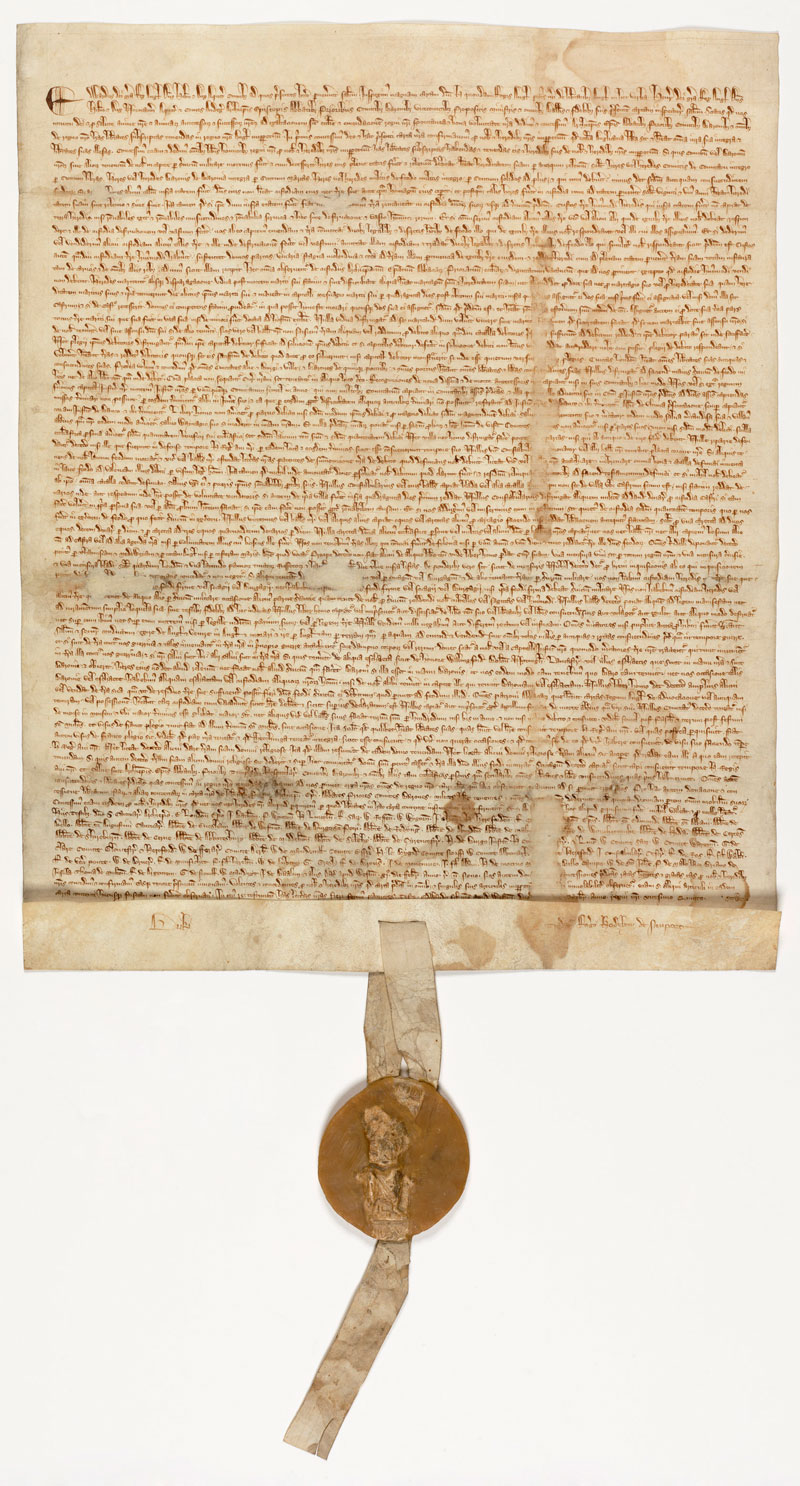

Magna Carta

Magna Carta was issued in June 1215 and was the first document to put into writing the principle that the king and his government was not above the law. It sought to prevent the king from exploiting his power, and placed limits of royal authority by establishing law as a power in itself.

It was written by a group of 13th-century barons to protect their rights and property against a tyrannical king. It is concerned with many practical matters and specific grievances relevant to the feudal system under which they lived. The interests of the common man were hardly apparent in the minds of the men who brokered the agreement, but there are two principles expressed in Magna Carta that resonate to this day:

“No freeman shall be taken, imprisoned, disseised, outlawed, banished, or in any way destroyed, nor will We proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.”

“To no one will We sell, to no one will We deny or delay, right or justice.”

Byzantine Empire

Part 1: Notable Places in Post-Classical Europe

Part 1.1: Venice

Culture & Trade

Venice was called the hinge between the east and west, where cultures collide and mix through trade. Venice was introduced to architecture and precious metals from trade with Islam. Venice was also the main connection with the silk road after the fall of Rome. Venice traded with the Mediterranean area by boat.

Venice was primarily Roman Catholic just like most of Italy. They spoke primarily latin but merchants attempted to learn arabic to better trade relations with the Islamic people.

Venetian scholars printed many Muslim discoveries such as medicine, philosophy, astronomy and mathematics.

Venice thrived off of trade with the Islamic world, in fact Venice might not have become very rich and popular without Islamic trade.

Venice traded salt, wood, linen, wool, velvet, Baltic amber, Italian coral, fine cloth and slaves to Egypt, Anatolia, the Levant and Persia. In return Venice recieved Silk, spices, carpets, ceramics, pearls, crystal ewers and precious metals

(from: https://prezi.com/aqpwxi3p-avf/post-classical-venice/)

Activity

Locate and identify the notable places mentioned so far on a map. You can use this one or one of your own.

Part 1.2: Cordoba

Geography

Córdoba city is the capital of Córdoba provincia (province), in the north-central section of the comunidad autónoma (autonomous community) of Andalusia in southern Spain. It lies about 80 miles (130 km) northeast of Sevilla.

Its area is divided by the Guadalquivir River into a mountainous north, crossed by the Morena Mountains, and a fertile, undulating southern plain, known as La Campiña.

Agriculture includes cereals, olives, and grapes, sheep, horse, and bull breeding, predominateli in the south. In the north the province’s chief industries are mining of lead, zinc, and coal. Furniture making and the production of metals and chemicals are also significant. The historic provincial capital, Córdoba, is an administrative center and popular tourist destination.

History before 1200

In 711 Córdoba was captured and largely destroyed by the Muslims. Its recovery was impeded by tribal rivalries until ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I, a member of the Umayyad family, accepted the leadership of the Spanish Muslims and made Córdoba his capital in 756. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I founded the Great Mosque of Córdoba, which was enlarged by his successors and completed about 976 by Abū ʿĀmir al-Manṣūr. Though troubled by occasional revolt, Córdoba grew rapidly under Umayyad rule; and after ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III proclaimed himself caliph of the West in 929, it became the largest and probably the most cultured city in Europe, with a population of some 100,000 in 1000. Under Umayyad rule, Córdoba was enlarged and filled with palaces and mosques. The city’s woven silks and elaborate brocades, leatherwork, and jewelry were prized throughout Europe and the East, and its copyists rivaled Christian monks in the production of religious works. Under the caliphate, Muslim Spain was the most populous and prosperous country in Europe. Increased irrigation produced an agricultural surplus which, with manufactured luxury goods such as Cordoban leather, Valencian pottery, and Damascus steel arms, and woven silk from Toledo. It was exported mainly eastward. When the caliphate was dismembered by civil war early in the 11th century, Córdoba became the centre of a contest for power among the petty Muslim kingdoms of Spain.

History 1200 to 1450

Corboda- “This is preposterous, I am getting invaded from all sides, even my fellow Muslims!” E. Roman Empire- “First time?”

After 1000, the collapse of Cordoba was inevitable. In 1009, the palace city of Medina Azahara became looted and then destroyed. In the 1020s, the political structure collapsed and the so called Taifa Kingdoms separated from the caliphate. The astable rest of the caliphate became vulnerable to Christian attacks.

The year 1236 marks the begin of the Christian era in Cordoba. On June 29th of that year, Ferdinand III entered the city and retook the power. Cordoba became a center of activity against the remaining Muslim population. Dozens of churches and monasteries were erected over the following period.

In 1486, discoverer Christopher Columbus decided to live in Cordoba. He planned to bid for royal support for his intended expedition to the Indies, but the monarchs, Ferdinand II and Isabella I gave permission to travel not before April 17th, 1492.

After Ferdinand II and Isabella I had beaten and expelled the last Moors, the so called Reconquista (recapture), including forced proselytization of people of different faith.

The Reconquista is a period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula, spanning approximately 770 years, between the initial Umayyad conquest of Hispania in the 710s and the fall of the Emirate of Granada, the last Islamic state on the peninsula, to expanding Christian kingdoms in 1492.

In 1236 C.E., immediately after the fall of Cordoba this magnificent mosque was converted into a Catholic church. It fell to the Castilian king Ferdinand III and became part of Christian Spain.

It remained a Christian military base in the frontier warfare against the Muslim kingdom of Granada, but the substitution of Spanish for Muslim rule hastened the city’s economic and cultural decline, and the fall of Granada in 1492 left Córdoba a quiet city of churches, monasteries, and aristocratic houses.

(Adapted from: https://www.britannica.com/place/Cordoba-Spain)

Activity

Locate and identify the notable places on your map.

Part 1.3: Kievan Rus

Kievan Rus, first East Slavic state, reached its peak in the early to mid-11th century.

Both the origin of the Kievan state and that of the name Rus, which came to be applied to it, remain matters of debate among historians. According to the traditional account presented in The Russian Primary Chronicle, it was founded by the Viking Oleg, ruler of Novgorod from about 879. In 882 he seized Smolensk and Kiev, and the latter city, owing to its strategic location on the Dnieper River, became the capital of Kievan Rus. Extending his rule, Oleg united local Slavic and Finnish tribes, defeated the Khazars, and, in 911, arranged trade agreements with Constantinople (Modern day Istanbul, Turkey).

Vladimir I (Volodymyr) came to power in 980. Kievan Rus still preserved its connections with other parts of Europe, however, and it ruled a large territory that stretched from the northern lakes to the steppe and from the then uncertain Polish frontier to the Volga and the Caucasus.

Vladimir’s reign heralded the beginning of the golden age of Kievan Rus, but that era’s brilliance rested on an unsteady base, as the connection between the state and its subject peoples remained loose.

The people paid tribute to the prince’s tax collectors, but they were otherwise left almost entirely to themselves and were thus able to preserve their traditional structures and habits. One development of enormous importance during Vladimir’s reign was his acceptance of the Orthodox Christian faith in 988. After this traditional religious practices were suppressed in Kiev and Novgorod.

Although the religion came from Constantinople, the Bible had been translated into Old Church Slavonic by missionaries in the 9th century.

Activity

Locate and identify the notable places on your map.

Part 1.4: Hanseatic League

Hanseatic League was an organization founded by north German towns and German merchant communities abroad to protect their mutual trading interests. The league dominated commercial activity in northern Europe from the 13th to the 15th century. (Hanse was a medieval German word for “guild,” or “association,” derived from a Gothic word for “troop,” or “company.”)

The origins of the league are to be found in groupings of traders and groupings of trading towns in two main areas: in the east, where German merchants won a monopoly of the Baltic trade, and in the west, where Rhineland merchants (especially from Cologne [Köln]) were active in the Low Countries and in England. The league was largely controlled by the towns, notably Lübeck, which had a central position and a vital interest in trade between the Baltic and northwestern Europe.

During the 14th century the Hanseatic League was not a true political federation, and it was not a true corporation. It had no permanent governing body, no permanent officials, no permanent navy, no central treasury, and no central court. It was “governed” by a diet that met irregularly, and the conduct of routine affairs was gradually transferred to the town council of Lübeck.

The diets were assemblies of delegates from the various towns, and their decisions (Recesse) were determined by a majority vote of the towns represented. In practice the smaller towns, eager to avoid the financial burden of an embassy, entrusted their interests to the representative of some larger town. In general, it was the views of a small group of leading cities that determined the policies of the league.

(Adapted from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hanseatic-League)

Activity

Locate and identify the notable places on your map.

Part 2: Notable People

Part 2.1: Margery Kempe

Margery Kempe left behind the first autobiography ever written in the English language. As a result, the events of her life are easily available to us, prompting many different viewpoints and analyses. For some, Margery was a proto-feminist figure, whose visions and close relationships with God offered her a level of agency that was not typically available for Medieval women. For others, Margery was the victim of a lifelong mental illness that plagued her with visions, delusions, and suffering.

Margery Kempe was born circa 1373 in Bishop’s Lyn, now King’s Lynn, Norfolk, England. The daughter of John Brunham, a well-off merchant, mayor, and Member of Parliament, Margery’s upbringing was unique. As Margery suggests herself in her autobiography, she was used to the finer things in life, wearing “gold pipes on her head”, and colored cloaks

Part 2.1: Marco Polo

Marco Polo was a Venetian explorer known for the book The Travels of Marco Polo, which describes his voyage to and experiences in Asia. Polo traveled extensively with his family, journeying from Europe to Asia from 1271 to 1295 and remaining in China for 17 of those years.

He was born circa 1254 in Venice, Italy, and died January 8, 1324.

After those 17 years in Khan’s court, the Polos decided it was time to return to Venice. Their decision was not one that pleased Khan, who’d grown to depend on the men. In the end, he acquiesced to their request with one condition: They escort a Mongol princess to Persia, where she was to marry a Persian prince.

Polo’s stories about his travels in Asia were published as a book called The Description of the World, later known as The Travels of Marco Polo. Just a few years after returning to Venice from China, Polo commanded a ship in a war against the rival city of Genoa. He was eventually captured and sentenced to a Genoese prison.

The book made Polo a celebrity. It was printed in French, Italian and Latin, becoming the most popular read in Europe. But few readers allowed themselves to believe Polo’s tale. They took it to be fiction, the construct of a man with a wild imagination. The work eventually earned another title: Il Milione (“The Million Lies”). Polo, however, stood behind his book, and it influenced later adventurers and merchants.

Part 2.1: Prince Henry

Henry the Navigator was born March 4, 1394 in Porto, Portugal and died November 13, 1460 in Vila do Infante, near Sagres.

Hewas a Portuguese prince noted for his money and support of voyages of discovery among the Madeira Islands and along the western coast of Africa.

The term Navigator was applied to him by the English although he himself never embarked on any exploratory voyages.

Part 2.1: Gutenberg

Johannes Gutenberg was born 14th century, Mainz [Germany] and probably died February 3, 1468. He was a German craftsman and inventor who originated a method of printing from movable type. Elements of his invention are thought to have included a metal alloy that could melt readily and cool quickly to form durable reusable type, an oil-based ink that could be made sufficiently thick to adhere well to metal type and transfer well to vellum or paper, and a new press, likely adapted from those used in producing wine, oil, or paper, for applying firm even pressure to printing surfaces.

(Adapted from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Johannes-Gutenberg)

Activity

Mark the birth place of these notable people on your map.

Part 3: Notable Events

Part 3.1: The Crusades (Circa 1095 – 1291)

There were a plethora of crusades undertaken, but most historians agree that nine primary crusades compose the Great Crusades. The first four Crusades are well known as they were the most impactful (successful and failure) and largest. Again, most historians would agree that after the Fourth Crusade, the Crusades were minor and made little impact on either side.

The Crusades Timeline and Dates:

- First Crusade: 1096-1099

- Second Crusade: 1145-1149

- Third Crusade: 1189-1192

- Fourth Crusade: 1202-1204

- Children’s Crusade: 1212

- Fifth Crusade: 1217-1222

- Sixth Crusade: 1228-1229

- Seventh Crusade: 1248-1254

- Eighth Crusade: 1271

- Ninth Crusade: 1271-1272

From: https://study.com/learn/lesson/crusades-timeline-history.html)

Part 3.2: The Little Ice Age (Circa 1250 – 1850)

Little Ice Age was a climate interval that occurred from the early 14th century through the mid-19th century, when mountain glaciers expanded at several locations, including the European Alps, New Zealand, Alaska, and the southern Andes.

The mean annual temperatures across the Northern Hemisphere declined by 0.6 °C (1.1 °F) relative to the average temperature between 1000 and 2000 ce. The term Little Ice Age was introduced to the scientific literature by Dutch-born American geologist F.E. Matthes in 1939.

Originally the phrase was used to refer to Earth’s most recent 4,000-year period of mountain-glacier expansion and retreat. Today some scientists use it to distinguish only the period 1500–1850, when mountain glaciers expanded to their greatest extent, but the phrase is more commonly applied to the broader period 1300–1850.

The Little Ice Age followed the Medieval Warming Period (roughly 900–1300 ce) and preceded the present period of warming that began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Little Ice Age is best known for its effects in Europe and the North Atlantic region. Alpine glaciers advanced far below their previous (and present) limits, obliterating farms, churches, and villages in Switzerland, France, and elsewhere.

Frequent cold winters and cool, wet summers led to crop failures and famines over much of northern and central Europe. In addition, the North Atlantic cod fisheries declined as ocean temperatures fell in the 17th century.

(Adapted from: https://www.britannica.com/science/Little-Ice-Age)

Part 3.3: The 100 Years War (1337–1453 )

The name the Hundred Years’ War has been used by historians since the beginning of the nineteenth century to describe the long conflict that pitted the kings and kingdoms of France and England against each other from 1337 to 1453.

Two factors lay at the origin of the conflict:

- The status of the duchy (territory of a duke) of Guyenne (or Aquitaine), although it belonged to the kings of England, remained a fief (and estate or land) of the French crown, and the kings of England wanted independent possession.

- As the closest relatives of the last direct Capetian (ruling house of France from 987 to 1328) king (Charles IV, who had died in 1328), the kings of England from 1337 claimed the crown of France.

(Adapted from: https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/hundred-years-war)

Part 3.4: The Black Death (1346 to 1353)

The Black Death was probably the earliest recorded pandemic. It took around four years to make its way along the Silk Road from the Steppes of Central Asia, via Crimea, to the Western most parts of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa.

In Europe alone it wiped out an estimated one to two thirds of the population. Many communities encountered the disease for the first time and had no idea how to respond.

The Black Death is believed to have been the result of plague, an infectious fever caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. The disease was likely transmitted from rodents to humans by the bite of infected fleas.

It is thought that the Black Death originated in Asia or Crimea and was spread to Europe by fleas on rats living on trade ships. In medieval times there was trade between Europe and Asia. The Crusades increased awareness of goods and produce that could be imported from abroad.

Common symptoms were the appearance of painful bubos ( inflammatory swelling of a lymph gland) hence the name bubonic plague, in the groin, neck and armpits. These later secreted pus and blood. These were followed by acute fever and vomiting blood. Victims usually died between two and seven days after being infected. The death rate was 60–90 per cent.

The medical authorities of the day had little to offer. ‘Leave quickly, go far and come back slowly’ was the general advice about what to do if an epidemic came to your town.

Activity

Create a timeline of the details and dates from one of the notable events above, or a broad one with all of the events, with less individual details. You can do this by hand or use an Adobe Template. See me for that.

Population Growth and Decline

Growth

Between 1000 and 1300 Europe’s population more than tripled from approximately 30 million to approximately 100 million people. Here are some theories and arguments for population growth in Europe during these times:

- Improving climate known as the Medieval warm period which resulted in longer and more productive growing seasons.

- The end of the raids by Vikings, Arabs, and Magyars, resulting in greater political stability

- Advancements in medieval technology allowing more land to be farmed, for example: the heavy wheeled plow, invented by the Slavic world, allowed for deeper plowing and better soil aeration. This made the wet European soil more productive.

- Due to the previous point: increased food production: The increased agricultural production led to a sufficient amount of food per capita. This allowed some people to become non-agricultural workers, which created a new division of labor.

- The reforms of the Church in the 11th century increased social stability.

- The revival of trade led to the growth of towns. Seaport towns, such as Venice and Genoa, served as trading centers.

Decline

The process of rural and urban expansion and development indeed paused in the 14th century as famine, epidemic disease, intensified and prolonged warfare, and financial collapse brought growth to a halt and reduced the population for a time to about half of the 70 million people who had inhabited Europe in 1300.

By 1450, the total population of Europe was substantially below that of 150 years earlier, but all classes overall had a higher standard of living.

- The Great Famine of 1315–1317. Little Ice Age, a decrease in temperature and a great number of devastating floods disrupted harvests and caused mass famine.

- The Black Death of 1347–1351

- International conflicts between kingdoms such as France and England in the Hundred Years’ War.

Activity

Good News! Bad News! It’s all news…

Write a newspaper article focusing either on the bad news of the imminent population decline for the people of Europe to be printed on the new Gutenberg printing press, or an uplifting opinion piece about the population boom.

It should be about 400 words, and contain dates, places, people, and events from the study.

It also needs to draw some conclusions of causality and suggestions for how it may affect people, places, and populations.

End of Project Quiz.

See Moodle Assignment.